Is Fascism Really On The Rise?

Is fascism really making a comeback?

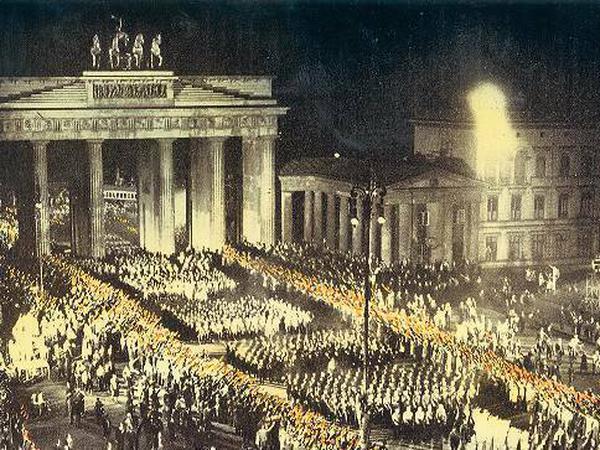

In recent years, I have observed (especially here, in Germany) that right-wing parties are gaining more and more popularity, such as the "right-wing conservative" and "nationalist" AfD (Alternative for Germany), but also small parties like the NPD (National "Democratic" Party of Germany) or the "Third Way", etc.So is it happening again, is fascism returning as it was in power in Germany in the 20s and 30s?

Of course, I cannot predict the future, but there is a kind of trend emerging, the national liberation of the Third World is progressing, the labor aristocracy in the imperialist motherland notices this and begins to act actively according to its class interest, as does the petty bourgeoisie. At present, however, things look less critical, why? I would like to explain this now:

A historical example:

"But the social strata and classes which promoted the Nazi ascendancy and their election successes on their way to power are not the ones which served the Nazis when actually in power. The class structure of the former must therefore be strictly differentiated from that of the second."

– The Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism, Alfred Sohn-Reithel, Free Association Books, London, 1987; S. 131

The petty bourgeoisie is economically backward because it lags behind the socially necessary average labor productivity. They are small, individual producers, some are self-sufficient (such as peasants), and many are small shopkeepers, etc. They were the early mass base of German fascism (as can also be seen, for example, in the "Harzburg Front," but more on that later).

What could cause this class to defect to fascism? The financial crisis in the 1920s or hyperinflation (we remember the almost surreal images of people trying to buy bread with wheelbarrows full of money!) liquidated a large part of the pension subsidies, savings and reserves of this class. Small shopkeepers, more often pensioners, small businessmen, etc. lost their money in one fell swoop. They were still saved from total liquidation, but often went into debt to the extremes, reducing their competitiveness. This lost competitiveness threatened many livelihoods; this process could be called the "proletarianization" of the petty bourgeoisie, as Reithel also mentions. (The Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism, Alfred Sohn-Reithel, Free Association Books, London, 1987; p. 132)

Many of these shopkeepers initially benefited from the Nazi regime's measures, for example, the forced hiring of the unemployed and the lowering of wages.

From here we must make a partial connection to the theory of labor aristocracy and dependency theory:

We know that part of the working class is "bourgeoisified," that is, it benefits materially from imperialism and the exploitation of the periphery (whether national or colonial plays a minor role here), through a "surplus of wages."

Reithel describes how at this time in Germany the "New Intelligentsia" was on the rise. This "New Intelligentsia" consisted mainly of engineers and technicians who supervised, installed, and kept large-scale production alive. Reithel explains here the role of this intelligentsia in capitalism:

"The ‘new intelligentsia’ in Germany occupied a problematic position between capital and labour and felt itself to be class-neutral. It stood, on the one hand, on the payroll of capital, on the same side as labour. On the other it was enlisted in the service of capital to be functionally dominant over the workers.

– The Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism, Alfred Sohn-Reithel, Free Association Books, London, 1987; S. 135

This forced the weakening industrial capital to enter into an alliance with fascism, especially since the KPD (Communist Party of Germany) was growing stronger and the other "bourgeois" parties were also weakened (here, especially the SPD, Social Democratic Party of Germany). So the industrial capitalists had to look around: "The bourgeois parties are failing, who will be our next candidate? The KPD? They want to expropriate and smash us! So only fascism remains!" Even though the two (industrial capital and fascism) could not really stand each other, they were welded together because of mutual necessity. The abolition of bourgeois laws also helped industrial capital to exercise its economic domination and recover from the crisis. Fascism, then, is a petty-bourgeois movement, a "Bonapartist" movement that was supported by industrial capital. "Bonapartist" because it created a state that fought against the organized labor movement and emerged at a time when the bourgeoisie was divided, disoriented and weak. Similarly in France after the 1851 coup, where the eponym of the term, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte III, ruled. The term itself comes from Marx's work, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.

Industrial capital in conflict

What makes Reithel's book so extremely good is his description of the conflict between German manufactory industry and heavy industry, the "Brüninger Camp" and the "Harzburg Front."

The Brüninger Camp consisted mainly of those interested in a traditional solution to the financial crisis of 1929, i.e., trying to revive international trade through treaties, loans, etc. An important representative of the Brüninger camp was Siemens. Siemens never had to fear bankruptcy during the financial crisis, like other companies (e.g. IG Farben), but Siemens was dependent on contracts with other countries, which gave the company a monopoly on the industrialization of these countries. Siemens was then allowed to build train lines, electrify infrastructure, and so on. However, the fight for these contracts was difficult and competitive, American, British and German companies literally fought for these contracts, accordingly the victorious powers of the First World War were pleased that Siemens was boycotted internationally due to Hitler's anti-Semitic policies and Siemens lost its supremacy in the international market. The corporate management was naturally outraged by Hitler's dictatorship. The way the crisis was handled also bothered Siemens; the corporation was based on the principle of "highest performance for highest price." However, the price-performance ratio of products depends not only on company strategies and costs, but also on currency policies and the relative price level of each country to other countries. Most international trade contracts were denominated in pounds sterling, all the more problematic for Germany when Britain took the pound off the gold standard in 1931. The world price level fell along with the pound, and the German mark was left with the island of inflated cost standards for its exports. Naturally, Germany did not want to follow Britain's path for fear that a wave of inflation like in 1920 would hit them again.

This problem became even worse when Hitler initiated reflation and absorption of the seven million unemployed by printing four billion Reichsmarks, raising the price level again. This policy led to a halt in factory rationalizations and a call for forced cartelizations.

In other countries, such as the U.S., this reflation was countered by a devaluation of the dollar, so the price increase remained in the U.S. and did not affect international competitiveness, Siemens even benefited from this devaluation of the pound and dollar in their respective regions, but this was not the case in Germany under Hitler, so competitiveness was severely affected. Hitler tried to counter this with a systematic lowering of wages, the seven million unemployed were hired below the wage level of 1931 ("Massenkonjunktur nicht Lohnkonjunktur" or "Mass economy not wage economy" as it was called in Nazi jargon).

Also important to mention is that Siemens had one of the most trained labor armies in Germany. They had excellent connections and relations with the workers' unions and tried to prevent Nazi penetration of those for fear they would sabotage relations. This then happened in 1935, with the Nazis dividing labor through racism and anti-Semitism and preparing the ground for the introduction of intensified exploitation.

Siemens' degradation to a mere arms factory of the Nazi regime followed; the arms contracts could not recoup the losses from being squeezed out of the international market.

Meanwhile, the other parts of bourgeois society came together in the Harzburg Front. Reithel's expression on this is very apt:

The overall position can be summed up by saying that, paradoxically, the ecnomically sound parts of the German economy were politically paralysed, whilst only those economically paralysed enjoyed political freedom of move.

On one side stood the petty bourgeoisie, which was on the verge of proletarianization, parts of the unemployed, plus civil servants and intellectuals. On the other side were the large corporations, such as Siemens, which helped try to resolve the crisis by traditional means through the Brüning government. Behind the latter camp, however, were also the big steel and coal industrialists, Flick, Thyssen, etc. How can this be explained now, why did these big industrialists pose as financiers of fascism and its "anti-capitalist" character?

After World War I, the German steel industry lost its position in the world; before that, it obtained huge contracts, be they armament or other contracts. Now, however, this source had disappeared. The steel industry fell into the subordinate position and to the front stepped the large manufactory industries like the chemical industry, electrical engineering industry etc.. (for example IG Farben and Siemens, both members of the Brüning camp). For the Stahlhof (the big steel cartel that united most of the big companies), therefore, a policy of rearmament was a good source of new contracts and thus new profit, likewise it could free its production plants from the chains of the market and exploit the full potential of the labor armies.

German monopoly capital was seen as deeply divided, somehow they had to be welded back together, otherwise they might run the risk of being destroyed by the communists. Now this is where the MWT - the Central European Economic Day - comes in:

If anyone contributed to the expansion and unification of German finance capital, it was the MWT. Krupp in particular was a very special member here, as a company with special vertical and horizontal organization, from manufactures to heavy industry, Krupp held many industrial sectors firmly in its hands. Furthermore, Krupp was completely financially independent, the company was passed within the family and no debts were ever incurred with others. Krupp was able to resist the policy of the Harzburg Front for the longest time, occupying a special place as a "crossroads" within the antagonisms of German finance capital. Thus, Krupp also helped to reshape monopoly capital - with a view to imperialist expansion, in the form of war. (The Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism, Alfred Sohn-Reithel, Free Association Books, London, 1987; pp. 47f.)

Industrial capital thus needed a government that would raise the rate of profit, which could only be achieved by lowering wages, which the Papen government did for the first time in 1932. The unions and the workers accepted the first wage cut because of the hopelessness of the situation. However, when the second wage cut was decided, there was fierce resistance - the class struggle intensified. The KPD led spectacular strikes that became increasingly militant; the strike involving some 20,000 transport workers in Berlin was particularly important. As a result, the Communists gained 700,000 new votes in the November 6, 1932 elections, while the NSDAP lost two million votes. This immense defeat shocked the industry, here it came to the point where they asked themselves. "If the masses do not defect to the NSDAP where will they go... (To the KPD, of course!)"

This struggle was also marked by the slow disintegration of the Social Democrats and the rather stronger appearance of the Communists. The SPD attacked the KPD while the KPD declared the SPD to be "social fascists."

However, all this progress was destroyed with the formation of Hitler's government. Immediately after the seizure of power, the trade unions were slowly disintegrated (for example, through the "Gleichschaltung"), and with the Enabling Act, the National Socialists were able to increase their supremacy over their big-bourgeois partners. After that, on May 2, the policies that were supposed to save capitalism were implemented, such as the wage policy.

Without the division of industrial capital and thus monopoly capital, the long anti-democratic history and the precarious situation of the economy, or the intensified class struggle, there would probably hardly have been fascism as we know it today. Instead, it is more likely that the "classical" bourgeois parties would have been in power. Now, however, we would like to draw parallels to the present day and consider the extent to which fascism is relevant today.

Modern fascism

Well, we can state that at present, due to corona pandemic, there is a crisis. But this crisis is not like the financial crisis of that time or like the hyperinflation of 1920 or the First World War. The bourgeoisie is not divided, it is not disoriented, the petty bourgeoisie is not really impoverished.During the 2008 crisis, there was a brief rise of fascist parties in countries like Greece, when unemployment rates rose in Greece in 2012, the fascist party "Chrysi Avgi" ("Golden Dawn") won many votes. However, a fascist coup did not occur. Not much happened in the other imperialist countries either. The bourgeoisie always prefers bourgeois democracy, it is the perfected rule of the bourgeoisie, only in emergency, only in crisis it needs brutal repression, corperatism etc. There is a slow rise of right-wing parties in general (which is a worrying trend, but we are still far from the 1929-1933 situation), but these are not comparable to the fascist parties of that time, they are still "bourgeois" at their core, they are not like the early NSDAP.

By the way, this is not to say that anti-fascism is not necessary, but many leftists exaggerate with the term "fascism", they do not see the phenomenon of fascism that we could observe in Germany or Italy (or ggbfs. Japan etc.), they relativize the term. In the future, of course, there could be a resurgence of fascism, but it is questionable whether this will really take the form of National Socialism, which is rather unpopular and relegated to the background in today's fascist scene. In the book "Confronting Fascism," Hamerquist explains today's new fascist scene, and I quote:

"However unfortunate it was for him and his organization, Pierce's categorical critique of U.S. society in the Turner diaries provided part of the impetus for the reemergence in the U.S. of the Strasser/Rohm "socialist" wing of fascism, the so-called "third position"-a fascist variant that presents itself as "national revolutionary" with politics "beyond left and right." (There seem to be two different wings of the Third Position. One calls itself the International Third Position, ITP, and tends to be predictably racist, anti-feminist, anti-Semitic, homophobic, etc. There is also a distinctly religious character to their politics. The other wing calls itself "National Revolutionary" or "National Bolshevik" and is much more radical; it categorically attacks "Hitler's fascism" and goes out of its way to argue that they support all movements that are truly anti-capitalist. Some National Revolutionaries, such as the NRF in England, are still blatantly racist and white-supremacist despite their support for certain liberation movements, such as the Irish and Palestinian. Others, as indicated in some quotes I will present later, claim to reject white supremacy altogether. Various national revolutionary groups and ideologues also have differences about anti-Semitism that parallel their differences about racism and anti-imperialist national liberation. I would recommend that one look at the material of both groups. This can easily be done by starting from the "Americanfront" and "International Third Position" websites)."- Confronting Fascism Discussion Documents For A Militiant Movement, Don Hamerquist, J. Sakai, Anti-Racist Action Chicago, Mark Salotte, Kersplebedeb Publishing, Montreal; pp. 27f.

Hamerquist summarizes the struggle between fascist positions very well. Industrial capital will find its friends in times of crisis, e.g., when there are great national liberations and a resurgence of socialism in the periphery, and thus the rate of profit again forcibly crashes, industrial capital will cooperate with the petty bourgeoisie-until it again imposes measures that destroy the petty bourgeoisie, much as the NSDAP did from 1933.

In Germany, the classically "national socialist" parties tended to move into the background - this development would thus be similar to the USA and Great Britain. Thus, a movement is brewing again, which rather takes a position to the early NSDAP, the so-called "left" fascists. For example, the so-called "national revolutionaries," who are politically more aligned with the "Strasserists" of the NSDAP at the time. For example, they support national liberation movements in colonized nations, for example, Ireland, Palestine and the Basques, or even Austria, which is considered "occupied" and apparently somehow organically supposed to be a part of Germany.

"They rely on an old tenet of right-wing dissent in Germany - the belief that a "Third Way" between capitalism and socialism is necessary and that Germany is predestined to lead humanity there. The NRs' "Third Way" is based on nationalism, a socialism "of the specifically national kind" - in short, a "national socialism.""None of these parties, however, has any great relevance whatsoever; even the Republicans, who were relatively relevant barely two or three decades ago, have disintegrated and been liquidated into today's AfD, which is also losing a bit of relevance at present. None of these parties, however, are truly "fascist," but they do have notable links to fascists such as the NPD:

"The Republicans, a political party founded in 1983 by former Waffen SS member Franz Schönhuber, have repeatedly denied any connection to the Nazis - they present themselves as nothing more than a "community of German patriots." But that does not stop them from taking explicitly anti-immigrant positions, especially against Turks, or from exploiting discontent over the influx of foreigners in general, or from claiming that Germany should be "for Germans." The presence of a "tidal wave" of asylum seekers in the Federal Republic, they believe, causes "the importation of criminals," "social tensions" and "financial burdens.""- Eco Fascism Lessons From The German Experience, Janet Biehl, Peter Staudenmeier, Edinburgh, 1995.

"The National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD), founded in 1964 primarily by people who had been active Nazis before 1945, rose to prominence in the 1960s. This aggressively nationalist party long called for German reunification, while its programmatic literature laments that "two wars within one generation ... have eaten away at the material health of the German people." (What these wars did to the Jews is not mentioned, as Ditfurth dryly notes.) The NPD laments the destruction of the environment, which "has adverse effects on public health." Germans should not be exposed to "chemical dyes" and should be protected from "hereditary diseases," while AIDS sufferers should be "subject to registration." The "preservation" of the "German people" requires that German women give birth more often, so the NPD opposes the "devaluation and destruction of the family." Since abortion threatens "the biological existence of our people," women who have abortions should be punished. The party calls for maternal and home economics education for "female youth.""- Eco Fascism Lessons From The German Experience, Janet Biehl, Peter Staudenmeier, Edinburgh, 1995.

Also noteworthy is the focus of many modern fascist parties on environmentalism. Many "eco-fascist" and "eco-völkisch" parties have also emerged, which attempt to combine, for example, (social) Darwinism with environmentalist or environmental preservationist policies.

The conclusion

Once again I can only appeal to the people, fascism only prolongs a system that is doomed to failure anyway because of its internal contradictions. The future is still - and will be - the introduction of the communist mode of production, enforced by the dictatorship of the proletariat, through revolution.At present we are not in such an acute crisis which could split monopoly capital and therefore prepare the ground for fascism. What is worrying, however, is the danger that the petty bourgeoisie will again be driven to the brink of proletarianization, as happened in 1920.

It is also important to note that the "old" National Socialism is a very dead movement, and fascism will most likely emerge in a form that we have not seen before. This has already happened in other countries, in the periphery, a concrete example of which would be Iran, where the Islamic government or the Islamic revolution went through the same path as the NSDAP and also had the same mass base.

Some final words: This is the second version of my former article. I have polished it up a bit and changed a few things. The German version of this entry is available here. I want to specifically thank my two friends for discussing with me and bringing me to the topic idea. I decided to write about fascism after a discussion in my city's local Pizza Hut after we thoroughly discussed politics (again).